Will the World Ever Speak a Universal Language?

It's a fascinating concept.

One language, spoken by everyone, enabling communication between any two people.

For most, the intent behind a universal language isn't to replace Chinese, Spanish, English, Arabic, or German, but rather to supplement these languages.

The idea is that this global tongue would be spoken in addition to our native languages, so that, theoretically, a Spanish speaker from Lima and a Chinese speaker from Guangzhou could understand one another.

In this light, a universal language seems enticing; it presents an opportunity to boost world harmony and international peace.

But is this overly idealistic?

In this blog, we'll draw on historical events, societal factors, and the intrinsic features of human existence to evaluate the possibility of a universal language.

Esperanto: An Overview

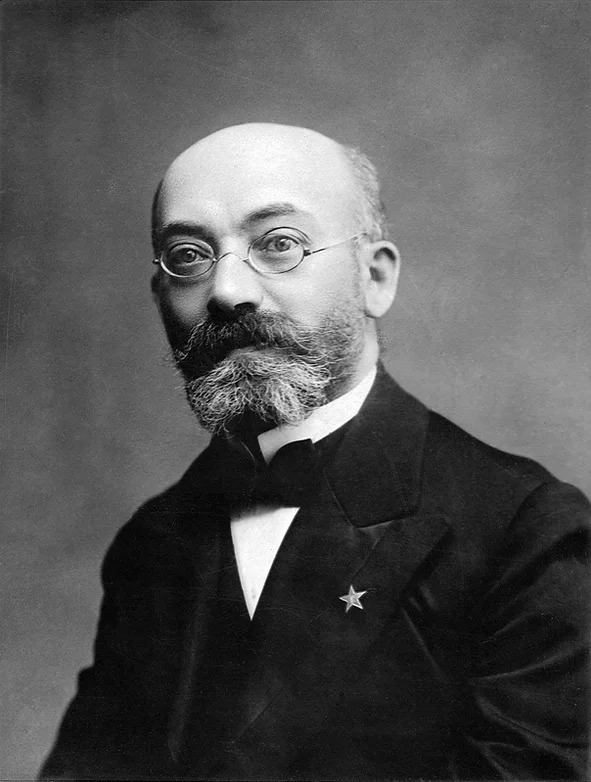

In 1887, Ludwik Zamenhof constructed the language of Esperanto.

It was predominantly based on European Romance languages, with its roots in Latin and influences from German, English, Russian, Italian, and Polish.

During his life, Zamenhof became fascinated by the idea of creating a world free from violence and war.

Being Jewish in Poland at the time gave him good reason; anti-Semitism was on the rise, shown by Russia's pogroms (violent attacks on Jews).

Zamenhof was a physician, but also an avid polyglot, speaking Russian, Polish, Yiddish regularly, and learning Italian, Spanish, English, Lithuanian, German, French, Hebrew, Latin, Aramaic, and Volapük - another constructed language invented in Germany almost a decade before.

People often forget that, initially, Esperanto caught on.

Societies were formed, books were published, and, most significantly, Neutral Moresnet (a small state between Belgium and Germany) declared it as their official language, even changing its name to Amikejo, which is Esperanto for 'friendship'.

Zamenhof's dream seemed to be materialising ... until World War One.

Esperanto was abandoned, as it hadn't been able to prevent Europe erupting into war; Amikejo was annexed by Belgium (dissolving the only Esperanto-speaking state); Zamenhof passed away in 1917.

There was a brief revival attempt after WW1, and the League of Nations considered adopting it as their official mode of communication.

But this revival was quelled by the formidable opponents Esperanto would face during World War Two, namely Hitler (who claimed that Jews were using it as a method of world domination) and Stalin (who sent its speakers to Gulags).

Tragically, Zamenhof's children were killed during the Holocaust because of their Jewish heritage.

Is Esperanto Still Spoken Today?

Esperanto is far from dead; there are an estimated 2 million speakers worldwide today, including around 1,000 native speakers, despite it being intended as an auxiliary language.

It isn't an official language in any country, but there are Esperanto conferences held all over the world, Esperanto magazines and journals published, and even an Esperanto Duolingo course.

Many write it off as a quirky hobby for language learners, but Esperantists see it as much more than that ... they see it as a key to bypass political issues and cultural clashes, facilitating conversation, connection, and co-operation.

Problems & Issues With Esperanto

Firstly, Esperanto has a strong European linguistic bias, making it harder for speakers of Asian languages to learn.

This is demonstrated by the countries with the highest number of Esperanto speakers: Brazil, France, USA, Germany, Russia, Poland, and Spain - all of which speak European based languages

Secondly, the presence of a universal language, even an auxiliary (as Esperanto was intended), could lead to the extinction of many of our current languages.

UNESCO provide an interactive atlas of the world's most endangered languages, from vulnerable, to endangered, to extinct.

Language death is a very real phenomenon - on average, a language becomes extinct every two weeks.

Currently, some of the most critically endangered languages include Taushiro (spoken in Peru), Bishuo (in Cameroon), and Irish Gaelic.

Today, 43% of the (approximately) 7,000 languages spoken in the world are endangered.

Every time a language is lost, society loses an invaluable source of wisdom, history, and culture, never to be retrieved again.

The creation of a universal language would likely tip those languages already on the brink of extinction over the edge.

Thirdly, language is integral to identity.

Everyone's mother tongue - and specific accent derived from that - signifies much about their sense of self, and evokes a sense of belonging to a community.

It's why languages like Kurdish and Catalan are so important to their speakers; those languages are a means through which they can preserve that marker of ethnicity and identity.

Moreover, the differences between languages cause us to interpret the world differently, and, consequently, fashion different ideas and attitudes.

For example, the Pirahãs of Amazonian Brazil do not keep track of exact quantities in their language; it is hard to argue that they see the world from the same perspective as those living in Western cultures, where measurements of size, time, and money are essential to society.

Without these cultural differences perpetuated through language, the world would be a place of extreme conformity, lacking all imagination, creativity, and originality.

The image that springs to mind is one of a dystopian society, in which free, individual thought is restricted.

Of course, this is the antithesis of Zamenhof's dream, in which Esperanto is spoken as a second language, aiding communication and preventing conflict.

In reality, this is probably too idealistic of a vision ... but that also partly seems to be the point behind Esperanto, which roughly translates as "the one who hopes".

Its moment in the light may have passed, and visions of a universal language may be unrealistic, but Esperanto still inspires hope among many people today.

The future of the world may not lie in a universal language, but it does lie in embracing cultural difference.

Learning to spread this hope, and connect more deeply with others, regardless of birthplace, upbringing, or language, is a must in today's ever-more polarised world.

Want to kickstart your language learning?

Click here for Five Easy Tips To Learn Languages.

Post a comment