A Tale of Tourism & Tragedy: How Haiti Became The Poorest Country in the Western Hemisphere

Just before 5pm on January 12, 2010, the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince was hit with a 7.0 magnitude earthquake.

Over 220,000 people lost their lives, making it one of the deadliest natural disasters in human history.

For those who haven't experienced a natural disaster first-hand, it's nearly impossible to imagine the overpowering feeling of sheer helplessness.

In Haiti, the damage was so extreme due to the already poor-quality infrastructure - buildings are assembled quickly and cheaply due to a lack of regulations - and exacerbated by the regular hurricanes and tropical storms which occur along the Haitian coast, thanks to climate change.

Haiti has continued to suffer since the disaster. According to UNICEF, children suffering from severe acute malnutrition, a widespread issue in Haiti, are three times likelier to die from cholera.

More than a decade on from the earthquake, Haiti is still an extremely vulnerable country, lacking proper sanitation, medical, and education services.

It is also a country of contrasts - not in terms of a wealth gap, but in terms of tourism.

Every year, around 1 million tourists flock to Haiti. While this is a small figure compared to some other places, such as neighbouring Dominican Republic which received seven million tourists annually (pre-Covid), this should, in theory, inject a reasonable income to support the country's fragile economy.

But it doesn't work like that. Unfortunately, while there are plenty of tourists heading to Haiti, the majority of these arrive via massive cruise ships. This generates some revenue but few of these tourists will leave the safe, idyllic haven of beaches in Labadie, Jérémie, or Port-au-Prince, therefore limiting the money that gets invested in the local Haitian economy.

Simon Reeve demonstrates this succinctly on his journey around the Caribbean - click here, and skip to around 29 mins, 30 secs. He illustrates how these tourists only experience the regulated, fabricated, 'brocherised' side of Haiti, and miss out on understanding true Haitian culture.

As the poorest country in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region - and the entire Western Hemisphere - Haiti desperately needs every penny of investment. The stark contrast between luxury tourism and inhumane poverty is a troubling issue, seen in many other poor countries worldwide.

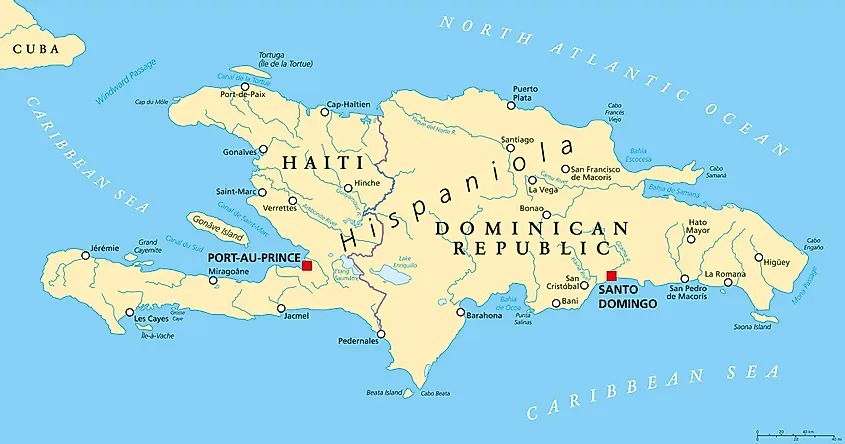

Despite sharing the island of Hispaniola, Haiti and the Dominican Republic have had a rocky past.

The Dominicans did nothing when France milked Haiti for coffee and sugar production, then demanded Haiti pay external debt for gaining independence. That was back in 1804, and Haiti were only able to finish repaying their debt to the French in 1947 - another factor behind their economic turmoil.

Lighter-skinned Dominicans looked down on the darker-skinned Haitians, a racial tension worsened by Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, who wore makeup to lighten his skin, and was obsessed with 'whitening' the mixed-race island of Hispaniola.

Chilling accounts of Trujillo's men massacring Haitians are infamous. In 1937, Dominican soldiers carried out the 'Parsley Massacre', asking any dark-skinned people to say the word "perejil" (Spanish for parsley); Haitians often found the "r" sound hard to pronounce, thus identifying themselves. This small slip of the tongue is said to have cost between 10,000 and 30,000 Haitians their lives at the hands of Dominican soldiers.

Haitian people also suffered at the hands of their own tyrannical dictator, François Duvalier, aka 'Papa Doc'. Duvalier's regime was characterised by corruption, human rights abuse, and an absurdly strong cult of personality. Near the end of his life, Duvalier faced a contracting economy, withdrawal of most U.S. aid, and a sharp decline in tourism.

In 2010, after the earthquake, the Dominican Republic was actually one of the first countries to rise to Haiti's aid, sending rescue workers, food, and water. The two countries of Hispaniola showed a fleeting sign of unity.

It was short-lived. Three years later, the Dominican Republic's highest court ruled to revoke the citizenship of children of illegal Haitian migrant workers. Just last month, more than 50,000 Haitians were deported with no chance to appeal.

Brewing tensions are worrying, as is the blatant Anti-Haitianism in the Dominican Republic, which stretches back decades, arguably centuries. And all of this is extremely damaging for Haiti's struggling economy.

Rather than uniting behind their shared history and geography, the two sides of Hispaniola remain split by a vicious, animosity-fuelled past. The outcome of this has negatively impacted Haiti, and is felt by its citizens every single day.

Life expectancy is only 63 years. 59% of Haitians live on less than $2 a day. This year, 86,000 Haitian children under the age of five face severe acute malnutrition.

Haiti is a breathtaking country filled with natural wonders, from soaring mountains to tumbling waterfalls. But it has been woefully mismanaged, both from a domestic and international viewpoint.

This brings us back to the age-old debate: is it morally acceptable to enjoy a holiday surrounded by abject poverty? One thing is certain - if travellers decide to visit places suffering from unimaginable hardship, they most make the upmost effort to inject money into the local economy.

Eat out at the local-run restaurant, not the big chain corporation. Buy clothes from a small, tucked-away shop off the main street, not the dominant household name brands. Truly make a commitment to learn about local culture.

Post a comment